‘On the first Saturday of every month, a book is chosen as a starting point and linked to six other books to form a chain. Readers and bloggers are invited to join in by creating their own ‘chain’ leading from the selected book.‘

Six Degrees of Separation: Kate W

I didn’t get on with this month’s starting book for the chain: No One is Talking About This, by Patricia Lockwood. In fact I got nowhere near finishing it, so my chain will go off immediately at a wrong tangent, as I understand the second half is very different from the first. I thought one reason I failed to engage with this book is that its protagonist is an extreme consumer of social media. And I don’t ‘do’ social media.

I decided, therefore that I would choose a hero who hasn’t even heard of social media, Hilary Byrd, of Carys Davies’ Mission House. Byrd, a slightly washed out, failed Englishman of middle years, is in India trying to escape from his pale and disappointing life. He finds himself in a town which is clearly Ooty, that haven for the English in Time of Empire. And it’s here that he meets The Padre, who offers him accommodation: and Jamshed, who becomes his driver. And Priscilla, the Padre’s adopted daughter. And Ravi, would be Country and Western singer, Jamshed’s nephew. This is the story of how their lives – all disappointing lives in many ways – come to intertwine. Beautifully written in short, sometimes apparently unrelated chapters, this is a book which had me immersed in the life and times of every character.

Byrd is not exactly a mainstream character. Neither is Charlie Gilmour, who tells his own story in Featherhood. This is an astonishingly readable book, which combines a tale of caring and raising a magpie fallen from its nest with a parallel account of Gilmour’s absent father. He too once raised a corvid, a jackdaw, but he was a far less reliable and responsible carer for his son – and several other children whom he fathered, while taking on few of the responsibilities of fatherhood. Charlie’s father, Heathcote suffered debilitating mental breakdowns and it becomes apparent to Charlie himself that he risks following the same trajectory: his late adolescence and early adulthood is peppered with difficulties which involve a spell in prison. This potentially weighty tale is leavened by accounts of the joy and mayhem which Benzene the magpie introduces to the lives of his whole family. As Charlie himself points out, Do Not Try This at Home. But his having done so has produced a delight of a book with a serious undertone.

The next book is fiction, told as autobiography, and it’s another chronicle of a life in crisis. Delphine de Vigan’s Based on a True Story. This is not a bed time story. Instead, it is a slow burn, of the kind the French seem so good at. Written in the first person, the narrator is a successful and respected author. She’s suffering from burnout, and this is the moment in which she makes a new friend – a friend who makes herself indispensable: a friend who begins to make her doubt herself: a friend who takes away any kind of belief in herself, slowly, skilfully and insidiously. It’s a deliberately uncomfortable read, and maybe perhaps just a little too long. On balance though, it was tautly constructed and I’ll read more from Delphine de Vigan.

We’ll stay in France, and meet a character who has difficulties of a completely different kind. It feels like an autobiography, and I sense that in large part, it may be. Fear, by Gabriel Chevallier. Over the years, I’ve read a lot of accounts of the common soldiers’ lot in WWI, and been both horrified and angry at the suffering and the waste endured. But this novel of French poilu Jean Dartemond is perhaps the most shocking I have read, and would have seemed especially so when it was published in 1930, when memories of those surviving, and their relatives, were still relatively fresh. No wonder publication was suspended during WWII. The day to day suffering, boredom and indignities, the all-too frequent horrors of witnessing disembowelled bodies, skin, bloated cadavers are described with a freshness that makes the horror very present. Towards the end, he describes how, when officers weren’t around, some German and French troops made tentative sallies of friendship across the divide, as they recognised how much more they had in common with each other than with their commanding officers, often remote and somewhat protected. This book, as so many others of its kind, is a true indictment of the horror and futility of war.

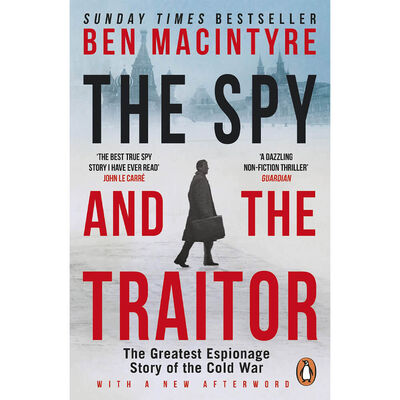

From WWII to the Cold War and its aftermath. The Spy and the Traitor by Ben MacIntyre. This is a thoroughly gripping and shocking book: the story of Oleg Gordievsky, KGB agent turned British spy. The picture painted of Russian society in pre-Gorbachev days, and of the day to day life of a spy, whose life must necessarily be cloaked in such secrecy that not even those you love the most – your wife, your parents – can in any way be privy to your true beliefs and loyalties is a deeply unsettling one. This is a fine and edge-of-seat story. Only it’s not a story. The life of a spy, the machinations of MI6 and the KGB among others, the story of the Cold War and the period after are all true, all recent history, and Ben MacIntyre explains it all well, and places it all in context. I was exhausted after finishing this book. But greatly illuminated by what I’d learnt too.

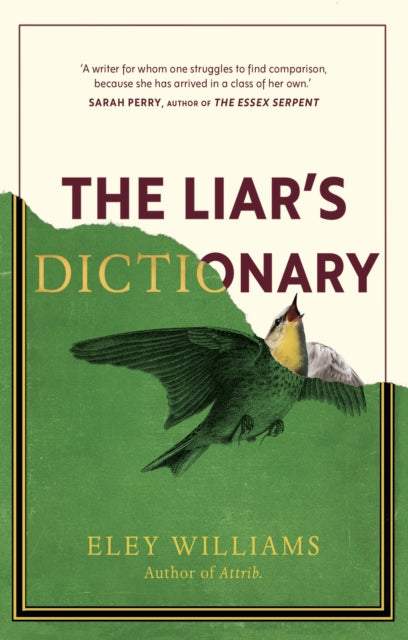

The life of a spy is, of necessity, the life of a liar. So let’s come full circle, and mention the Liar’s Dictionary by Eley Williams. Dictionaries are scarcely social media, but even now, they enjoy a long reach. I thought this book would be a sure-fire hit with me, as I’m an inveterate dictionary bowser. I tried this book once, and abandoned it after twenty pages. I tried it again, and grudgingly admired Williams’ pure enjoyment of, and fun with words, but on the whole it left me cold. This is the story of a dictionary, long in the making: and, in alternating chapters, the personal struggles of 19th century Winceworth, and 20th century Mallorie’s and their tussles with mountweazels – fake entries planted in works of reference to identify plagiarists. For a fuller account and more positive review, read here.

The book to start next month’s chain will be Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair. I haven’t read that in years. I’d better find a copy.

You must be logged in to post a comment.