We keep a mental list of the walks we’ve particularly enjoyed. Walks we’ve treasured for the views, the flowers, the butterflies, the skyscapes, the lunchspot – all sorts of reasons. The only problem is that the walk at the top of the list tends to be the one we did last. There’s no such thing as a duff hike round here.

But last Sunday’s walk is assured a place of honour on this list. It’s one we’ll want to share with you if you come to stay, and we’re keen to do it again ourselves, at every season of the year.

If you drive from here to Mirepoix, you’ll pass through a village called la Bastide de Bousignac. Just after that there’s a road off to the left, signposted to Saint Julien de Gras Capou. Take it. It’ll wind upwards between grassy pastures, home to sheep and cattle and not much else, and finally deposit you in the main street of the village – current population 62. Park near the church, lace up your walking boots, grab your rucksack with its all-important picnic, find the first yellow waymark – and set off.

The village is so-called because back in the 12th and 13th centuries, it had acquired a reputation as being the place where fine fat capons were raised to feed fine people: that’s the ‘gras capou’ bit. I don’t know where St. Julien comes into it. There are hens here still, and in so many ways, the village is perhaps little changed. It’s a peaceful, rather isolated place, despite being so near to Mirepoix and one of the main roads in the Ariège.

Our walk took us along farm and forest tracks, through fields and woodland still splashed with colour from flowers and late butterflies. It was an easy route, rising only gently, passing the tiny hamlet of Montcabirol towards the village of Besset. Shortly after that though, we found we did have a short sharp climb, through the woods, to reach the Pic d’Estelle.

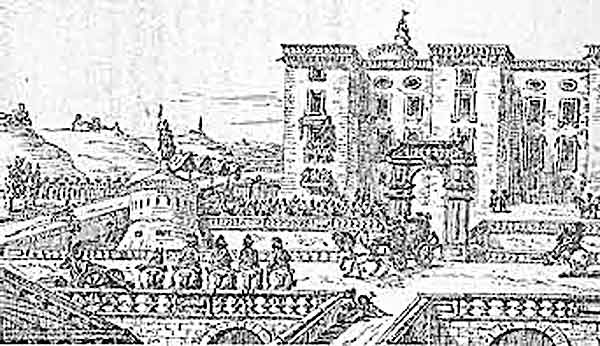

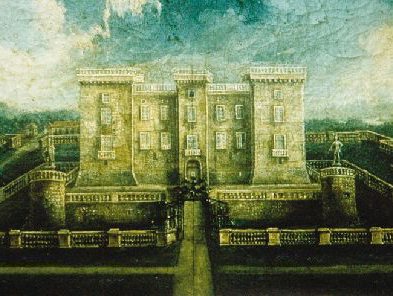

Wow. It was worth it. From here, we had a 360 degree panorama. The chain of the Pyrenees marched across our horizon, its peaks already dusted with snow, or even quite thickly covered in the case of the higher summits. As we turned in other directions, we could see Mirepoix, immediately recognisable from its distinctive cathedral spire, and the Montagne Noir beyond. There are foothills nearby too, across which pilgrims on the Chemin de Saint Jacques de Compostelle still travel: and other sights too – the ruined Château de Lagarde, and its near neighbour the Château de Sibra. We stayed a long time, simply relishing these views, the sky, the silence and peace at what seemed to us, at that moment, the top of the world.

When we finally shrugged on our rucksacks once more, we only had three or four more kilometres to go, along more unpeopled pathways. After negotiating the only obstacle of the afternoon, a group of cows supervised by a bull – we let them get well ahead of us – we were soon back at base. It was good, very good. I just wish my camera could do justice to those peaks. But we’ll be back, in winter, when they’re truly thick with snow

You must be logged in to post a comment.