On the first Saturday of every month, a book is chosen as a starting point and linked to six other books to form a chain. Readers and bloggers are invited to join in by creating their own ‘chain’ leading from the selected book.

Kate W: Six Degrees of Separation

I wanted to read the starter book for this month’s chain, Trust, by Hernan Diaz. But for some reason, the library hasn’t yet satisfied my reservation of it. So I’m working with Diaz’s own comment about his book: ‘there are very, very few novels that deal with the process of accumulation of capital. This, to me, was baffling.’

I have to say it doesn’t baffle me. But I thought I’d go with a short book that looks at a world where capital was – for large swathes of the population – in very short supply. A bit like today. The War of the Poor by Eric Vuillard was an International Booker Prize finalist in 2021. This is a vigorous and pacily written appeal for social justice, using the various Peasants’ Revolt type struggles of the Middle Ages, sometimes rooted in religious fanaticism to make its points. His focus is the life and times of Thomas Müntzer, German preacher and theologian, for whom even the likes of Martin Luther were too Establishment.

In a mere 60+ pages, he conjures the atmosphere of discontent of the peasantry with the oppression and poverty which was their lot. It was a fight that could not be won, and in vigorous, emotionally wrought poetic language, Vuillard tells the tale of what he sees as one of history’s great injustices.

From one political struggle to another. Red Milk by Sjón (translated from the Icelandic by Victoria Cribb). This is the story of Gunnar Kampen, who grew up in Iceland a towards the end of WWII in a family fiercely opposed to Nazi oppression. The story depicts a happy enough conventional childhood which progresses towards his job in a bank. And yet … he comes into contact with Fascist ideas and ideals, and soon becomes a leader of Iceland’s under-the-radar Nazi movement.

The book goes out of its way to portray Gunnar as a young Mr. Average, whose political proclivities are hard to spot in society at large, while pointing out those aspects of Iceland’s recent history that make it possible for Gunnar to entertain the views that he has. An unusual and compelling book, showing the mindset of a young man sucked into a belief system now regaining some political traction throughout Europe.

Gunnar is an unusual young man who presents as absolutely average. So does William, the young hero of A Terrible Kindness by Jo Browning Wroe. The tragedy of Aberfan is one that no Brit of my generation or older is likely ever to forget. That 116 children and 28 adults, all from the town’s primary school should lose their lives when a colliery spoil heap collapsed and buried them was shocking, even from afar. For 19 year old William Lavery, just-graduated embalmer who volunteers to go and help prepare the dead for burial it was traumatising, and coloured his life thereafter. It wasn’t the first traumatic event in his life. The first was when he was a boy chorister in Cambridge – and actually, he had trauma to deal with before that too, as a boy of 8. This is the story of how his life unfolds, switching back and forth between the years, unpicking the various strands of his story that depict the damaged young man he becomes, and his eventual slow redemption. Beautifully and engagingly told, this story deals with big, unmanageable emotions, and is one of those books about which I can say ‘ I couldn’t put it down’.

I read another book about Aberfan, several years ago. Owen Sheers‘ The Green Hollow. He paints a scene of ordinary families getting ready for the day, ordinary children chattering their way to school, an ordinary teacher taking the register. A series of letters explain why the Coal Board is taking no action about the slag heaps . And then …. a rumble, a roar develops. That is all.

Then we switch immediately to the rescue. To the young medical student who finds himself unwittingly part of the rescue operation, to the miners, parents, journalists.

Now the town is different. Life goes on. It has to. Children yearn to appear on ‘Strictly’ while every year commemorating what happened all that time go. Scars exist alongside hope. This is a moving, powerful, poetic account. It’s dignified, quiet and respectful, and a fine tribute to a town that’s had to deal with utter despair.

A book now about other towns which have irrevocably changed – because they’ve disappeared: Matthew Green‘s Shadowlands. Here is a totally immersive account of how certain villages and towns in England simply got wiped from the map. By placing his chosen locations in the context of their history, their geography and their climatic or political turbulence, he offers a surprisingly varied set of stories of obliteration, drowning, geological change, historical unrest. Every story is placed in the context of that community’s place in history, and offers a rounded, absorbing and detailed account of why and how these communities disappeared. A moving and haunting set of stories.

I wrote only a fortnight ago about – not towns and villages – but forests which have disappeared. Guy Shrubsole‘s The Lost Rainforests of Britain. You can read my review here.

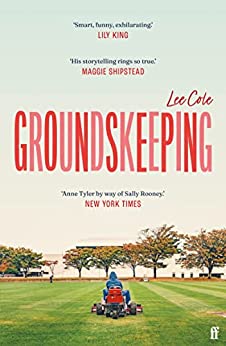

For my last book, I’ve chosen a story where our young hero is a groundsman at an American college, in a small team responsible for its trees and woodlands: Groundskeeping, by Lee Cole. A love story set in 2016-17 at a time when Trump and his ideas were in the ascendant, although he hadn’t yet been elected President. Owen’s from a working class Kentucky family, earning a wage as a groundsman at a college, while still trying to further his education and career as a creative writer. Alma came as a young child from Bosnia, and this refugee family has made good – very good. It’s this tension between their two backgrounds when they catapult into a relationship that informs the whole book, and is painstakingly examined throughout. I turned the pages willingly enough, but felt 400+ pages was far too long to sustain the plot, and was mildly irritated by Owen’s self-absorption throughout.

I seem to have travelled quite a long way from my starting point. Let’s see what we can all make of next month’s: the 1970s self-help classic, Gail Sheehy‘s Passages.

You must be logged in to post a comment.