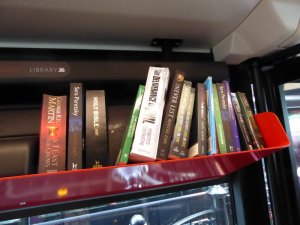

Everyone loves the 36 bus. It’s the one that takes us from out in the sticks of Ripon, via Harrogate to Leeds. It’s the one with plush leather seats, 4G wi-fi, USB points at every seat. It’s the one with a book-swap shelf where I always hope to find a new title to enjoy, while bringing in one of my own to swap. And best of all, we old fogeys travel for free on the 66 mile round trip.

Best get to the terminus early though. Everyone’s jockeying for the best seats, the ones at the front of the top deck, where you can watch as the bus drives through the gentle countryside separating Ripon from Harrogate, via Ripley, a village which the 19th century Ingleby family remodelled in the style of an Alsatian village, complete with hôtel de ville. After the elegance of Harrogate and its Stray, there’s Harewood House – shall we spot any deer today? Then shortly after, the suburbs of The Big City, which gradually give way to the mixture of Victorian and super-modern which characterises 21st century Leeds.

We had lots to do in Leeds today (more of that later, much later) and had a very good time being busy there. But much of our fun for the day came from sitting high up in that 36 bus, watching the world go by. For free.

You must be logged in to post a comment.