On our recent trip, mainly to Alsace, but with sorties to Germany and the Netherlands, we came across several stories from the past which we’d known nothing about, but found engrossing. For the next few Fridays, I’ll share these stories with you.

The Battle of Le Linge

Anglophone readers will all know the dreadful story of the so-called Great War, 1914 – 1918. Particularly the war in Flanders, with its trench warfare in which first the Allies, then the Germans, gained a few yards of ground, then lost it, and gained it again in manoeuvres that resulted in the pointless deaths of thousands upon thousands of men whilst upending the communities in which those battles took place, as well as the families whom they had left behind. It turns out that this story was repeated in very different territory too.

In the Vosges mountains, in territory which has through the centuries passed repeatedly between German and French hands there is a col known as Le Linge. It’s a mere 17 miles (28 km) from Colmar, but it’s a different, often desolate world, reached by travelling up apparently endless and steep hairpin bends which cut through dense forest and a rocky landscape untouched by human hands. On the day we went there, to visit the Mémorial du Linge, it was rainy: and I was glad. This was no site to enjoy in balmy sunshine.

Early on in the course of the war, both French and German commanders thought they could see advantages in taking control of Alsace, though both had sent the bulk of their troops elsewhere – notably the Marne.

Here’s what the Memorial’s own website has to say:

'Given the situation on the battlefield, the French army had to overcome enormous logistical difficulties . Starting from scratch, it had to build roads, camps, ambulances, aid stations, transport ammunition and supplies on mules, install heavy and light artillery, build battery emplacements, shelters and other necessary installations, and finally transport the combatants, all in full view of the German enemy.

Faced with such preparations, the latter would not remain inactive and would prepare for the coming assault. Taking advantage of the shelter of the forest, excellent logistics (notably a narrow-gauge train from Trois Epis) and the proximity of the Alsace plain, the German troops established solid defenses. Trenches, shelters and connecting trenches were installed on the mountain, fortifications built, pillboxes and machine gun nests arranged, fields of barbed wire unrolled along the steep slopes between trees, rocks, brambles and other chevaux de frise (movable obstacles, often made of a wooden frame with spikes). These defenses added to the complexity of the battle for the French forces and further accentuated their initial disadvantage on the terrain.'

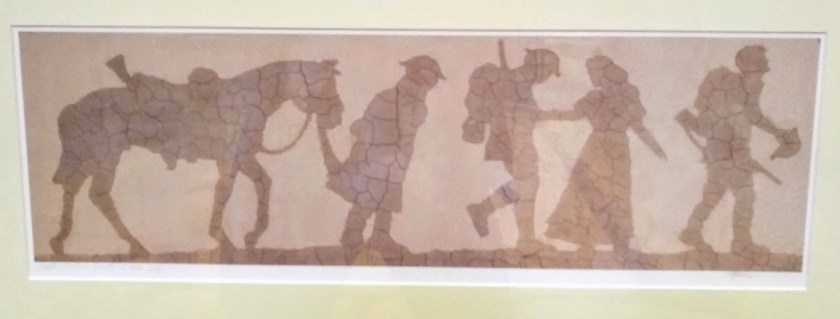

Both soldiers here look almost 19th century, equipped for different battles from the long-drawn out trench warfare to which they were actually subjected.

From July 1915, battle commenced. There were attacks, counter-attacks, hand-to-hand fighting as each side was only feet away from their enemy. I read one account in the museum, which I’ve been unable to find again, telling of a batallion going into battle one night with over 2000 men, and returning in the morning with just 3 officers, and 28 men.

Despite courageous resistance from the French, the German forces always maintained the upper hand. On October 16th, the last German assault took place, after which both sides retreated into an uneasy, exhausted, totally debilitated calm.

And yet. Both sides retained a pointless presence there for the whole of the rest of the war, with skirmishes a daily routine. On average, 5 men died every day during the whole of this period: young men, mainly aged 19 or 20. Specialised forces were deployed, such as these troops here: skiers. Whole villages were forced to evacuate, and many remained abandoned after the end of the war.

Yet again, the website sums it up:

'The Battle of Linge, of no strategic importance, was a true human tragedy marked by the courage, determination, self-denial, and sacrifice of French and German soldiers.

It bears witness to the brutality and difficulty of the fighting of the First World War, where thousands of lives were wasted for often minimal territorial gains.'

After the museum, it was time to go outside and inspect the trenches, still intact. We were reminded that those we see today would have then been about a metre deeper. As advised, I was wearing my walking boots – Malcolm wisely decided not to join me. I set off confidently on the ‘difficile‘ circuit, and after a degree of inelegant scrambling, retreated to the ‘moyenne‘, and finally to the ‘plus facile‘. The scenery was a treat: the terrain by turns rocky, slippy as gravel skittered away from me, slippery, steep, narrow, impassable. The trenches were cold, narrow, inhospitable, offering the occasional cave cut into the rock to offer shelter from rain, wind and- in winter – snow and ice. Winter temperatures there regularly fell well below freezing. On my walk I often passed a white cross, indicating a French corpse who had been found, or a black cross for a German. Both are now memorialised respectfully. It’s recommended that visitors take up to an hour and three quarters to discover the whole site. I did not. It was raining. I was neither a poilu*, nor a frontschwein**.

This was a thought-provoking day, and one which we shan’t forget, at a time when seeing images of war and its human consequences are still part of our daily routine.

*The French term for a infantryman, and actually meaning 'hairy man'.

** A frequent term for a German infantryman, meaning 'front pig'.

You must be logged in to post a comment.