On our recent trip, mainly to Alsace, but with sorties to Germany and the Netherlands, we came across several stories from the past which we’d known nothing about, but found engrossing. For the next few Fridays, I’ll share these stories with you.

Unterlinden, Colmar

Maybe this post will be a bit History-lite, but it’s still a story worth telling. Back in 13th century Alsace, the Dominican order founded a convent, Unterlinden, in the then outskirts of Colmar. The nuns from this contemplative order were woven into the life of the city until the French Revolution, when in 1793 the convent was confiscated. First abandoned, it then became a military barracks.

In 1846, something rather extraordinary happened. Louis Hugot, the archivist-librarian of the City of Colmar set about bringing together fellow intellectuals and enthusiasts with the aim of setting up a print collection and drawing school. They called themselves Societé Schongauer afer an Alsatian engraver and painter, an important influence on Albrecht Dürer. The following year, they bought the now-abandoned convent and bequeathed it to the city.

Its earliest display is still here: a locally-discovered Roman mosaic. Here it is.

Then, the museum made do with plaster casts loaned from the Louvre. Now, it has an impressive collection of sculpture and altarpieces from a variety of churches in the area.

I was quietly impressed by these displays. Simply presented against white-painted walls, these pieces spoke of their spiritual intent, and I spent a long time in their presence, for the most part alone.

These pieces were all acquired in the early 1850s. But the star of the show, then and now, and the reason why most people visit this gallery is to spend time with Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim altarpiece. As I did. But partly because I have no good images of it, and partly because it deserves a long appreciation, I won’t discuss it here. This is a good article from the Guardian –here.

Then there are the cloisters: just the place for more religious statuary.

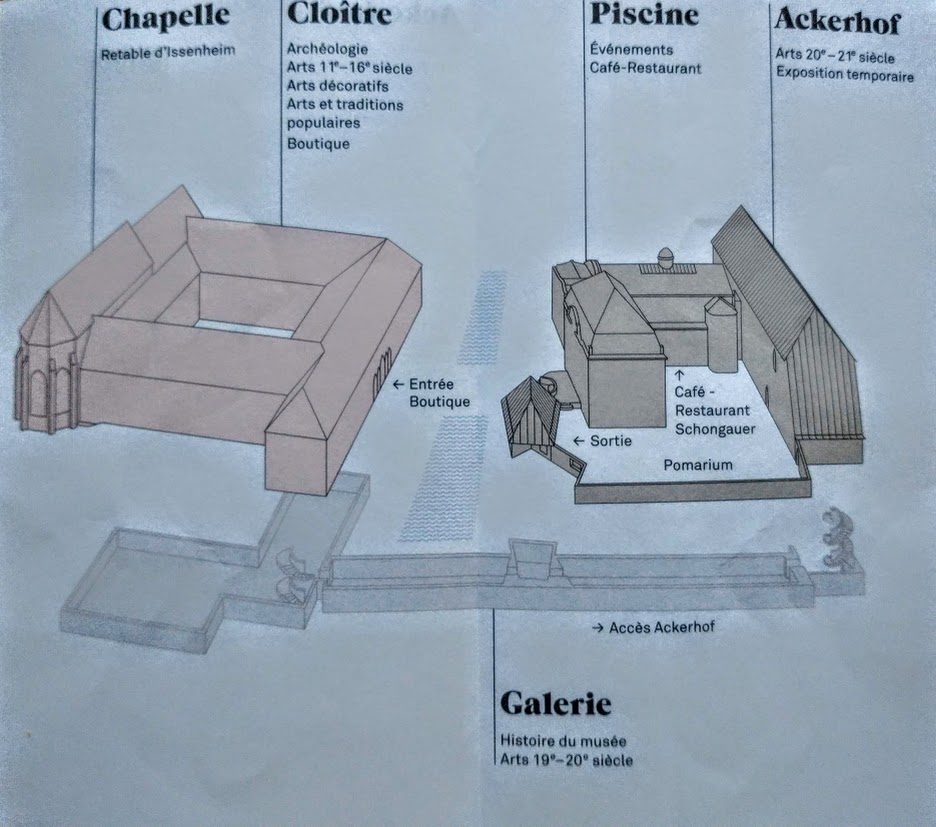

By the early 21st century the museum was running out of space. It was making contemporary acquisitions. It needed a refreshment area. Basel architects Herzog & de Meuron thought outside the box. The 1912 Public Baths on the other side of the road were no longer in use.

Why not connect the two buldings with an underpass which could also be a display area?

This is the result.

The result is a gallery where the works on display can breathe. Where the newer parts complement the old and reflect its religious past. It’s an exciting as well as a contemplatve space, and I put this gallery down as possibly among the best viewing spaces that I have ever visited.

I’ll finish by showcasing two or three of the works which appealed to me.

Just a postscript. Malcolm didn’t come with me. He thought he was too tired to be able to spend a few hours standing before a succession of art works. If only we’d realised. He could have made use, for free, of one of these flâneuses, or leisurely strollers. What a brilliant idea!

Becky, can you find the image + shadow for NovemberShadows? I hope so.

You must be logged in to post a comment.