On the first Saturday of every month, a book is chosen as a starting point and linked to six other books to form a chain. Readers and bloggers are invited to join in by creating their own ‘chain’ leading from the selected book.

Kate’s: Books are my Favourite and Best

I haven’t read the starter book, Tom Lake by Ann Patchett, which is set in small-town Michigan. Here’s how Book Browse summarises it: ‘Tom Lake is a meditation on youthful love, married love, and the lives parents have led before their children were born. Both hopeful and elegiac, it explores what it means to be happy even when the world is falling apart’. It sounds to me as though it also reflects upon how in the end we are alone, even if living in an established family or community.

Kent Haruf’s Plainsong is set in small town Colorado. This beautifully written, spare, stark book takes as its theme the loosely intermingled lives of various abandoned souls who live in the imagined town of Holt, Colorado. There’s teenage Victoria, pregnant and abandoned by her boyfriend; Tom Guthrie, whose wife has retreated into deep depression, leaving him with the care of his young boys, Ike and Bobby; the elderly McPheron brothers; infirm Iva Stearn. These isolated people display dignity and stoicism in their difficulties, and struggle towards some sense of connection and community. Holt seems a pretty bleak town, and the landscape that surrounds it too. Haruf’s descriptions are always understated, always telling. His characters maintain their privacy, whilst allowing us to care about the ultimately optimistic conclusion of the book.

From a bleak town to a bleak continent: let’s go to the Arctic with Christiane Ritter: A Woman in the Polar Night. In 1934, Ritter, a painter, left her ordinary life with a teenage daughter to join her husband in his life as trapper in Arctic Spitsbergen. It turns out to be as cold and inhospitable as we all imagine, and twice as primitive. Home is little better than a shack, the stove is primitive and unreliable, and all fuel needs to be found and collected by them, The same applies on the whole to food. They have only a few basic supplies. Animals and birds have to be caught and processed, and these fatty unfamiliar meats form much of their diet. Husband and Norwegian friend and housemate are often out trapping, looking for animals whose fur they will sell. That’s enough to tell you what much of this book is about. It’s twice as tough as it sounds in this unforgiving climate. But it’s beautiful too, and Ritter dwells on this. Straightforwardly yet engagingly written, this book offers an insight into the strange world which she chooses for a year to inhabit, and leaves reluctantly.

Here’s another book about a woman alone: The Diver’s Clothes Lie Empty, by Vendela Vida. This book is written in the second person, and it distances us from a protagonist who wants to stay distant. She’s a young unnamed woman who’s come – fled perhaps – from Florida to Casablanca. Checking into her hotel, her backpack with all her important documents is stolen. The police ‘find’ it, but it’s not hers, the woman whose documents it contains is not her. But she accepts it. In many ways, losing her given identity suits her. She soon changes her identity again… and again. Her need for anonymity runs deep, perhaps partly from her wish to escape her own face, disfigured by teenage acne. Perhaps because of what we come to know of her story – no spoiler alerts here though. Through what little agency she has, she time and again shifts the ground beneath her feet. This is a novel of profound unease and bewilderment, and distancing our heroine from us by simply calling her ‘you’ is a part of that bewilderment. An unsettling reading experience – recommended.

Nahr is another isolated woman, who tells her (fictional) story in Susan Abulhawa’s Against the Loveless World. A powerful story, told by Nahr, a Palestinian woman in solitary confinement for an unnamed act of terrorism. Her time in the Cube, as she calls her cell is recounted in short chapters interleaved with longer accounts of her life thus far. Much of her early life was spent in a Kuwait ghetto where many Palestinian refugees, dispossessed by the Gulf War fetched up. After an unsuccessful school career, Nahr works hard at menial jobs to save up so that her brother can avoid her fate by going to medical school. She meets an older Kuwaiti woman who blackmails, prostitutes but also loves her, propels her into high-end prostitution. Marriage to a freedom fighter saves her reputation – and his – but he’s a closet homosexual who soon deserts her for his lover. I don’t want to reveal more of the story, but eventually she returns to Palestine and finds close relationships and a political awakening that changes her life forever. This timely read, detailing the brutal legacy of Israel’s ongoing occupation of Palestine is both powerful and thought-provoking. Though it is of necessity one-sided, it should be required reading for anyone wishing to understand recent Palestinian history. The shock waves of recent events continue and escalate.

Isolation seems to be developing as a bit of a theme here. Here’s isolation of a completely different kind. Orbital, by Samantha Harvey. Six astronauts (two of them are cosmonauts), all from different countries, some male, some female, orbit the earth in their International Space Station. We visit them for one day only, as they travel 16 times round the globe. We experience with them the wonder of this journey: the brush-stroke beauty of the landscapes they view from afar, as well as tiny detail – headlights, fishing boats. We accompany them as they go about their often mundane daily experimental tasks. Or using the treadmills that are part of their daily routine. Or we see their sleeping bags, billowing in weightlessness: the spoons they eat with, attached by velcro to the cabin wall. We perceive aspects of their life back on earth – children, a loveless marriage, a trusting partnership. The book moves through the spectacular and the ordinary, distance and intimacy and invites us, the readers, to wonder too.

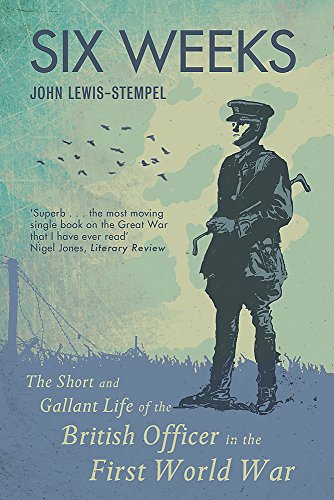

Wonder at the earth? Let’s look at Meadowland: The Private Life of an English Field, by John Lewis-Stempel. An utterly absorbing account of a year in the life of an English meadow. From harsh January, through the months in which warmth and life returns, to busy summer and autumn and back to chilly dormancy again, John Lewis-Stempel notices and absorbs everything. He sees birds, insects, animals and plants in microscopic detail. He relishes smells, tastes and sights. He enters fully into the life of his traditional meadow, one that may have existed for many hundred years. A celebration of traditional country scenes, leaving the reader with a campaigning zeal to preserve the rich variety of life it contains if sympathetically managed and left to itself. As he himself says: ‘To stand alone in a field in England and listen to the morning chorus of the birds is to remember why life is precious.’

Isolation seems to be a theme here. Will that continue next month, when we’re invited to start our chain with a favourite travel guide?

My first five photos come courtesy of Unsplash: Alexander Andrews; Levartravel; Vince gx; Annie Spratt; Gallindo Bailey. The final shot is my own.

You must be logged in to post a comment.