On our recent trip, mainly to Alsace, but with sorties to Germany and the Netherlands, we came across several stories from the past which we’d known nothing about, but found engrossing. For the next few Fridays, I’ll share these stories with you. And oops. Last Friday I quite forgot what day of the week it was. So here, a whole week late, is a Friday Footnote.

The Nuns of Thorn

Our German friends live very near the Dutch border, so on our first day with them, they proposed an outing to Thorn, in Limburg. They promised a pretty little town with an interesting abbey. We got so much more than that.

Almost every town in Thorn is painted white – in fact it’s known as ‘The White Town‘ -more about that later. And the Abbey itself dominates the town. Nobody quite knows when it was built: but sometime in the 10th century. The bishop of Utrecht and his wife had it built for their daughter who became the first abbess of the convent. You thought Catholic priests were celibate? So did I. But apparently they could get away with marrying and fathering children at the time, despite official disapproval. Things only got tightened up a century later, when religious leaders realised that wealth was being passed down to sons and daughters rather than to the church.

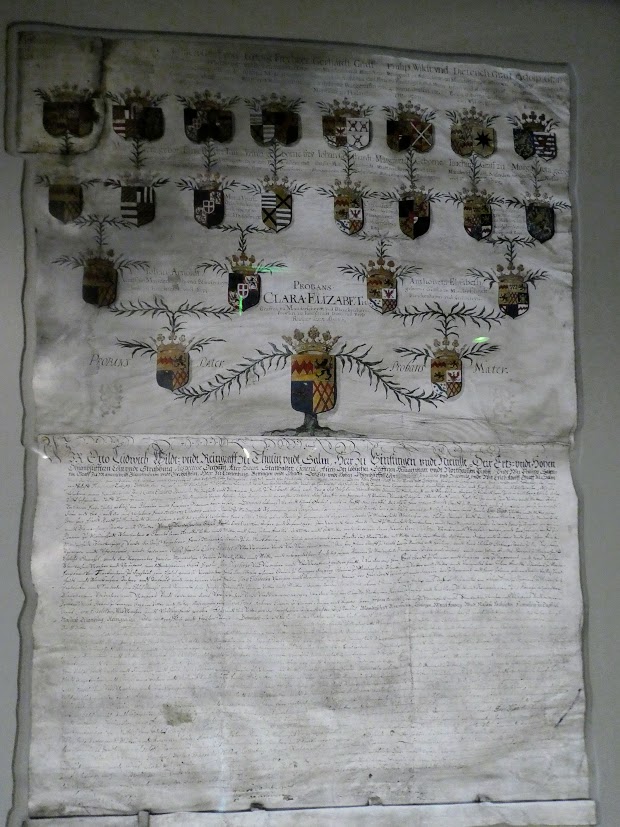

Put aside any thoughts you might have that a convent was a place for pious women who wanted to live a simple life of devotion to God. The abbess was assisted by a chapter of six to twelve ladies from the aristocracy who brought with them – and could keep – all their earthly possessions. They were therefore able to accrue land over a wide area, which they farmed out for huge profits. The convent turned into an elite place where one could be accepted only if both parents, and all grandparents up to the great-great-grandparents on both sides were of noble birth. Impoverished nobility need not apply. Here is an example of the kind of family tree needed to prove eligibility:

By day, the canonesses could stay in their homes in Thorn, with their servants and worldly goods, returning to the convent only at night to sleep. Even this rule was abandoned. They petitioned the pope in 1310 to be allowed to relinquish their sombre black tunic with a white wimple.

But they had to wait 180 years for this request to be granted. Though once it was, this was what a nun here might look like:

Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

By the end of the 15th century the abbey was granted ‘imperial immediacy‘ which turned it into an Imperial Abbey within the Holy Roman Empire. In the 16th century the abbess already had one seat in the district council of Westphalia and in the 17th century a seat in the discussion forum of the Empire, known as the Imperial Diet, giving this (relatively) tiny abbey an important role within Europe. It was actually an independent city-state.

All this brought prosperity to Thorn. Lands were farmed out, and although the peasants paid rent, no taxes were levied: This was just as unthinkable then as now. In the 16th century, the abbey even had its own mint. Till it was shut down, when it was discovered the coins’ silver content was falsified, and was too low.

The French Revolution put a stop to all this. The Low Countries were invaded and fell under French Rule. In 1796, all religious establishments were abolished, and even though the abbess tried to argue that as the nuns didn’t live together it wasn’t a religious establishment, it was all in vain. The palace of the abbess and all abbey buildings were demolished. Only the Abbey Church survived.

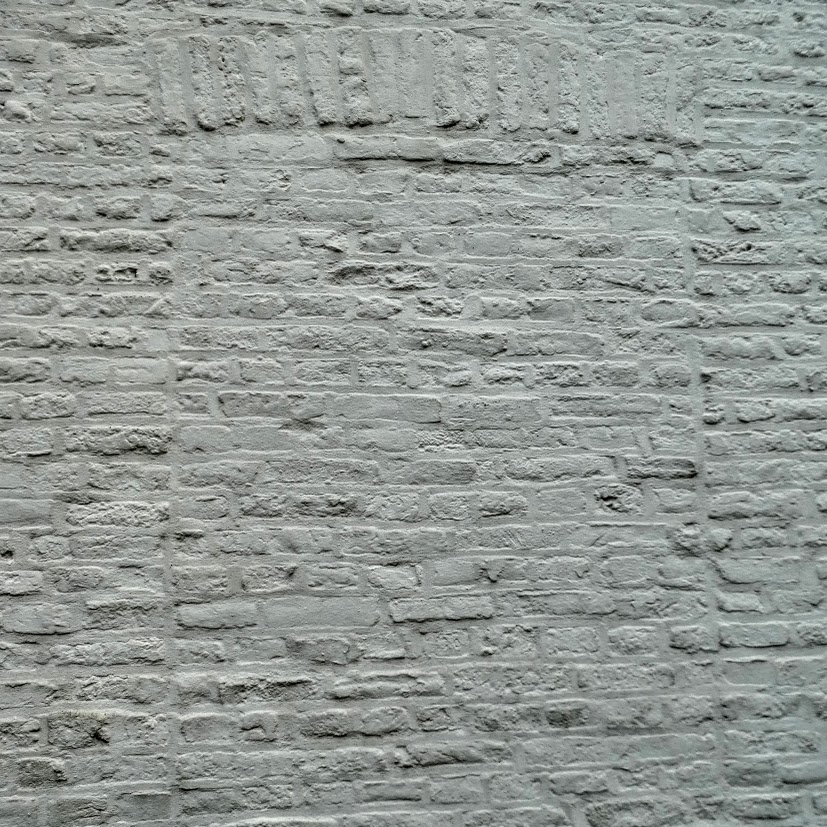

Thorn became part of France – Meuse-Inférieure. The French didn’t like the fact that Thorn was a tax-haven, and started to impose taxes. One of the taxes was based on the number of windows a house had. So …inhabitants of Thorn bricked up the windows to pay fewer taxes. And to cover it all up, they whitewashed the walls of their houses, to conceal the scars.

Thorn became a white town. Here in Britain we also had a much-hated window tax, in force between 1696 and 1851. It may be the origin of the phrase ‘daylight robbery‘.

Thorn remained part of France until 1815 when at the Congress of Vienna it was given to the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. But it remained, then as now, a White Town.

So there we have it: a town of powerful women (whether God-fearing or not I don’t know), of economic prosperity for all, and free of taxes. Well worth a detour for any travellers to Limburg.

For Becky’s NovemberShadows today, look for the ‘shadow’ of a window in Thorn.

You must be logged in to post a comment.