On our recent trip, mainly to Alsace, but with sorties to Germany and the Netherlands, we came across several stories from the past which we’d known nothing about, but found engrossing. For the next few Fridays, I’ll share these stories with you.

Ammerschwihr

We happened upon Ammerschwihr on our way back from Le Linge and decided to stop, attracted by its mediaeval town gates.

It’s a prosperous little town. This commune is home to the highest number of winegrowers in relation to the number of inhabitants anywhere in Alsace. And that’s saying something.

As we mooched round, it gave the air of being yet another pretty town of half-timbered houses. Until we reached the old town hall, which these days doesn’t even justify being called a facade.

Then a small plaque. Oh! So it was destroyed during the war?

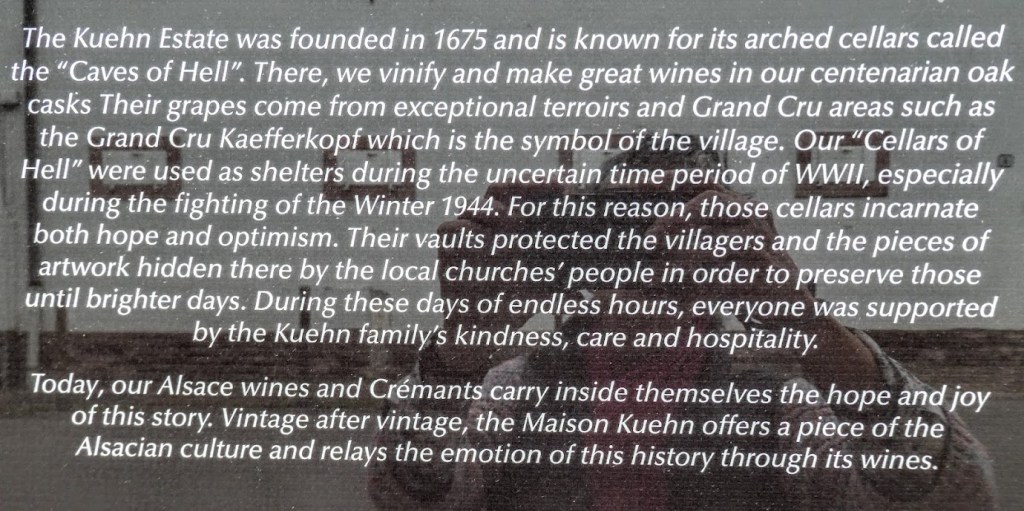

Buildings nearby were clearly more modern, though sympathetically built to fit in with the ancient centre (which we later realised were also reconstructions). We found another notice, attached to the wall of one of the many wine producers in town.

We needed to know more.

During the later stages of WWII, The Battle of the Bulge was the Germans’ last attempt to break through Allied lines. They gained a dangerous amount of French territory in a campaign which though apparently well known, I hadn’t heard of. The Allies promptly regained much of this territory, except in an area near Colmar, which became known as The Colmar Pocket. Ammerschwihr was in this zone, and like so many other nearby communities, it lost 85% of its buildings to bombing raids in December 1944.

But the ins and outs of military campaigns are above my paygrade, and if they interest you, you can read about them here and here. I prefer to know what life was like for the women and men on the street. Although I read that the conditions for the serving soldiers during this part of the war were truly horrendous. A particularly harsh winter in 1944 – 45 meant that both sides endured the sheer misery of fighting in deep snow and mud in totally inadequate clothing. Getting supplies to them was a sometimes unachievable struggle. Casualties were extremely high.

For the civilians, life was no better. Ammerschwihr wasn’t evacuated, but many villages were, and unending columns of the dispossessed trailed to what they hoped was safety, having lost everything but the little they could carry. Those who remained faced street barrages, hand-to-hand fighting. Food and often water were hard to come by, and the population hid in cellars, sharing what little they had. For those of us whose territory wasn’t invaded during WWII, this suffering is almost unimaginable. And afterwards – the long hard road to reconstruction, and trying to re-establish some kind of normal life.

Here’s what it says in WWII History Tour: Colmar Pocket

Once under German control, Alsace was subject to forced Germanization policies. The use of the French language was banned in schools, public spaces, and even private conversations in many cases. Street names were changed, French cultural symbols were removed, and local populations were pressured to embrace a German identity, often against their will. Families with French allegiances were treated as enemies, and suspicion ran high among neighbours, with the region caught between two nations. The sense of belonging for Alsatians became deeply conflicted as they struggled to retain their unique Franco-German culture under oppressive occupation.

Perhaps the most devastating aspect of Nazi control was the forced conscription of Alsatian men, known as the “Malgré-nous” (meaning “against our will”). Thousands of young men were drafted into the German army, the Wehrmacht, and even the feared SS, despite many feeling a strong allegiance to France. Some were sent to fight on the Eastern Front, where casualties were extremely high. Families were torn apart, and many Alsatians who tried to resist conscription faced imprisonment, deportation, or execution. After the war, the return of Alsace to France did not immediately heal the scars. The region carried the burden of divided loyalties, lingering mistrust, and the painful memories of occupation and forced service, which shaped its identity for decades to come.

It was hard to reconcile all this with the charming, civilised, peaceful little town we wandered around. The nearest we got to the unpleasant realities was this building, once a town gate, once in fact a prison, and known as Le Tour des Fripons – the Tower of Knaves. It all seemed much less immediate than the town’s more recent disturbing history.

You must be logged in to post a comment.