On the first Saturday of every month, a book is chosen as a starting point and linked to six other books to form a chain. Readers and bloggers are invited to join in by creating their own ‘chain’ leading from the selected book.

Kate W. – Six Degrees of Separation

Somehow, I didn’t read I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith when I was younger. And I’ve only just managed to source a copy, so I haven’t read it in time for Six Degrees. This is how it’s introduced in Goodreads. ‘Through six turbulent months of 1934, 17-year-old Cassandra Mortmain keeps a journal, filling three notebooks with sharply funny yet poignant entries about her home, a ruined Suffolk castle, and her eccentric and penniless family. By the time the last diary shuts, there have been great changes in the Mortmain household, not the least of which is that Cassandra is deeply, hopelessly, in love’.

That seemed to chime with a book I’ve just finished, Natasha Solomon’s Fair Rosaline. This is a re-interpretation of the Romeo and Juliet story from the stand-point of bit- character Rosaline. To be fair, the story of bereavement, infatuation, love and bereavement again zipped along, but even as a page-turner, the narrative quickly became increasingly unbelievable. The characters were something of a caricature and the language veered unconvincingly between the Shakespearean and more modern idiom. If you want a reasonably page-turning beach read, this could be for you. I made the link to our starter book because Rosaline could well have lived in a castle (though she didn’t). And she falls hopelessly in love.

One thing you’ll notice if you read Fair Rosaline is that a fair few characters die. So my next book is A Tomb with a View, by Peter Ross. This is an evocative, delightful and thought-provoking book. Yes, it’s about death and burial. But the variety of cemeteries, ways of remembering the dead and rituals Ross explores is astonishing. He’s clearly a sympathetic man to have around, and historians of ancient cemeteries, gravediggers, Muslim celebrants, natural burial enthusiasts, proponents of The Queerly Departed all willingly open up to him and bring their own special Final Resting Place to life. He visits graveyards, charnel chapels, cemeteries and so much more, animating them in a delightful tribute to these sites and those who work there and care for them. A book to read with – yes – enjoyment.

From death, to near death, in Maggie O’Farrell‘s I Am, I Am, I Am. This is not an autobiography, but a non-chronological exploration of the author’s 17 (seventeen!) brushes with death, each episode named for a different part of the body. Attacks at machete-point, nearly-road-accidents, a dreadful experience of childbirth: all these and more are graphically and tenderly brought to life. Most affecting is the last quarter of the book, where she describes her own debilitating and long-running experience of the after-effects of a virus: and then her daughter’s even worse experiences. It’s compelling, sometimes angry, often visceral. She’s graphic at describing pain, fear, despair. Impossible not to experience at least some empathy for O’Farrell and her experiences. And yet she’s still here, bringing her experience to bear on her other work, in which she brings fictional characters and their dramas to life, informed no doubt by her own experiences.

And now from one non-chronological memoir to another: Sandi Toksvig’s Between the Stops. Marvellous. I was suspicious of a book written by something of a National Treasure. It would play to the gallery, surely? I was wrong. This is part memoir, part political polemic from someone whose views I’m happy to share, part social commentary and part Interesting Facts About London and the many places she’s called home. She uses the device of a journey on her most familiar bus route, the Number 12 from Dulwich to central London to gaze out of the window and use the memory triggers she finds as she observes the scene there, or among her fellow passengers to introduce the story of her life in America, Denmark and England. She’s witty, compassionate, angry and introspective by turn, and always amusing, often laugh-out-loud funny. I loved this book.

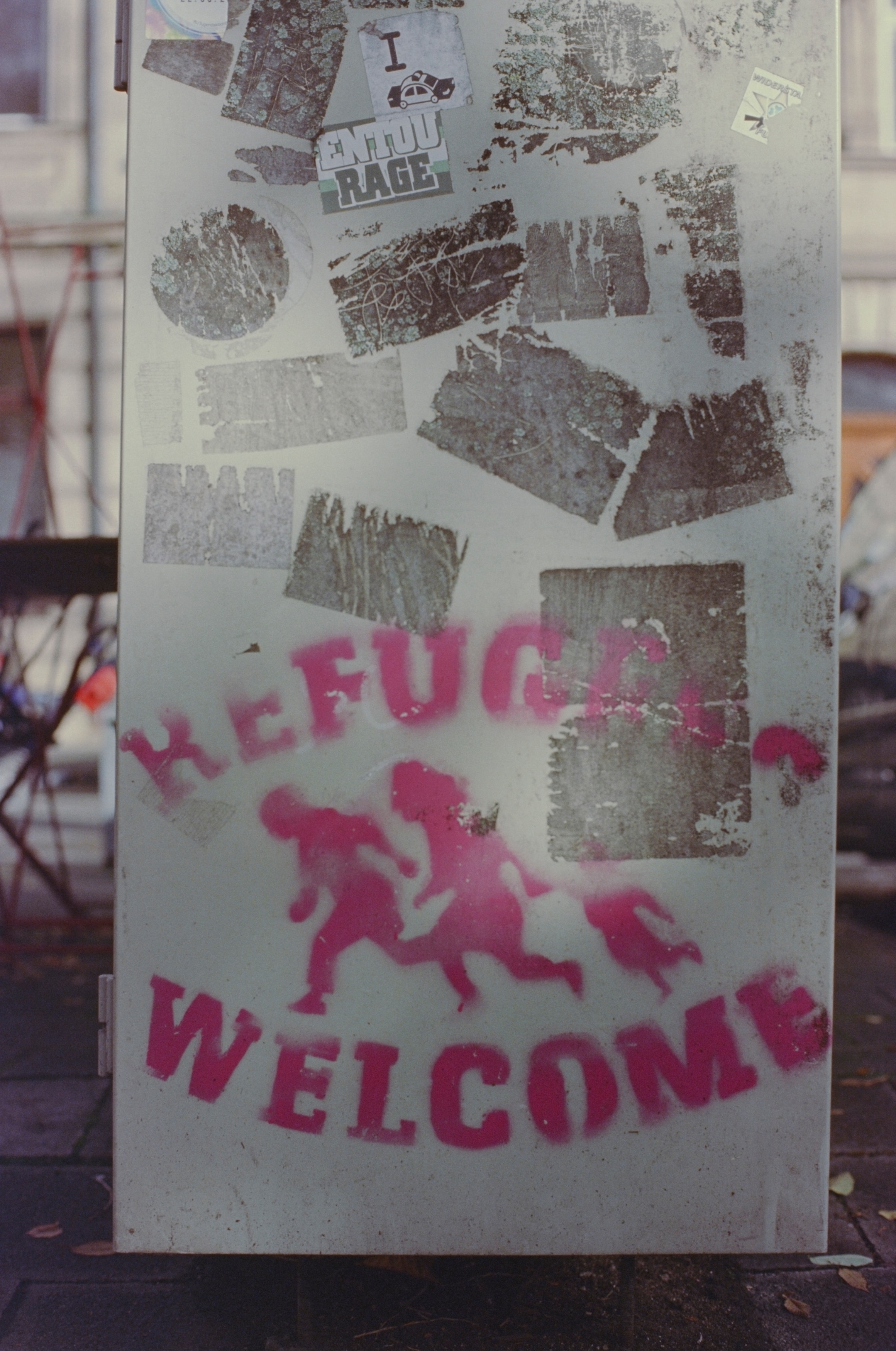

My next choice also uses London as a starting point. The End We Start From by Megan Hunter is a powerfully unsettling novella. Here is a world descending into chaos and uncertainty just after the ‘author’ has given birth, in London. This is the story of a fleeing into the unknown from a city that’s no longer functioning following an unspecified apocalyptic disaster. Sparingly and beautifully written this is a short, eloquent and potent account of one woman’s fall-out from a not too unlikely future catastrophe. But one which does not finish on a note of despair, but of love.

Lastly, let’s go back to the 14th century: a time when England, like much of Europe, was turned upside-down socially by the predations of the Black Death, as well as by war, and it must have felt like the end of the world. Barry Unsworth’s Morality Play. Nicholas Barber, a young cleric who has abandoned his post and fallen in with a band of itinerant players tells his story. What brings this story its power is its power to immerse the reader in the life he’s – at least for the time being – chosen. This band of players live from hand to mouth, often cold, always dirty, always on the move and wondering where the next meal and billet is coming from. But they devise the idea of re-enacting a shocking murder that has just taken place in the community in which they find themselves, and discover that all is not as it seems. And add fear of the more powerful to their list of worries. An immersive tale, bringing the sights, smells, sounds, and mores of the 14th century to life.

Well. We have wandered about a bit. Each book links, if tenuously, with the next: but there is no common thread running through these choices.

And next month, Kate invites us to read as our starter book Western Lane by Chetna Maroo. Are you going to join in the fun?

You must be logged in to post a comment.