On the first Saturday of every month, a book is chosen as a starting point and linked to six other books to form a chain. Readers and bloggers are invited to join in by creating their own ‘chain’ leading from the selected book.

Kate: Books are my Favourite and Best

This month, I have to begin where I left off last time, with Nicola Upton‘s Nine Lessons. I described it here, so now I’ll confine myself to saying it’s a detective story set in Cambridge.

So. To another detective story set in Cambridge, and one I read a long time ago. I’m always up for reading Kate Atkinson, but it took me a while to try the Jackson Brodie series. Then I read Case Histories. In many ways I enjoyed this unusual approach, in which several different lives and families from Cambridge are introduced, long before a crime becomes apparent. Yet inexorably and inevitably they come to the attention of private detective Jackson Brodie. I found some of the characters stereotypical: mad-as-a-hatter cat-lady; eccentric middle aged sisters and so on – there are more. Jackson solves everything, inevitably, but more by luck than judgment. There were so many characters I got somewhat muddled. I seem to be damning this book, yet at the time I turned the pages easily.

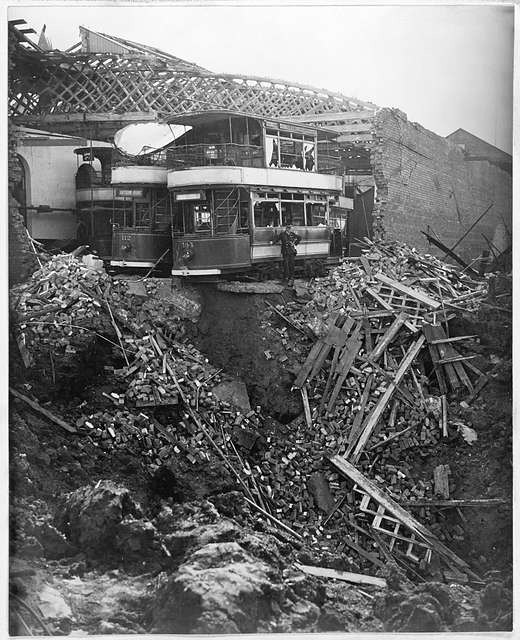

Let’s try Kate Atkinson in different form in Shrines Of Gaiety. She takes us to 1920s London, to a place of hedonistic gaiety where Nellie Coker is queen of a whole series of nightclubs, each appealing to a different kind of pleasure-seeker. Her family is essential to her enterprise and the story, with two Cambridge educated daughters (a Cambridge link again!) and a twit of a son in the mix of six. Add in a Yorkshire librarian on furlough, two young Yorkshire runaways, police officers who are variously dutiful and bent and you have a complicated and atmospheric Dickensian yarn. I enjoyed it: This is Kate Atkinson after all, but I also found it a little wearisome and forced, with not all the characters well-developed. I read through it quickly and with some enjoyment, but also feeling somewhat cheated of Kate Atkinson at her best.

From one form of public entertainment to another. Kenneth Wilson’s Highway Cello. It’s an account of Kenneth Wilson’s decision to load a cello onto the back of a trusty old bike and cycle from his home in Cumbria, via England, France and Italy to Rome, playing to impromptu audiences in town squares, and lightly-planned concerts in homes, halls and cafes. In among this part of the tale, he discusses the whys and wherefores of his trip, and always with a light touch. It’s an uplifting, amusing and undemanding book, the perfect accompaniment to a holiday: that’s why I’ve only just read it. Though it’s a couple of months since he came to our local Little Ripon Bookshop, played his cello and read from his book with verve and good humour.

Wilson ends up in Rome. Another British writer, Matthew Kneale lives in Rome. And he wrote a pandemic diary, The Rome Plague Diaries. I loved it. Having many years ago lived in Italy, though not in Rome, this put me back in touch with many aspects of Italian daily life and culture. It also revived memories of Lockdown – not unwelcome ones: I was one of those who actually relished many aspects of it, because of where and how I’m able to live. If you’ve enjoyed Kneale’s writing; if you love Italy, I recommend your reading this vivid account of a resilient city going through yet another test of its mettle.

The only other story I’ve read set during the pandemic is Sarah Moss’ The Fell. I read it when I was self-isolating with Covid, probably in early 2021. Kate and her teenage son, living in Cumbrian fell country were quarantined at home. Kate, frustrated, eventually goes out, to get up there on the moors, at a moment when there won’t be a soul about, and be back in time for tea. Except she isn’t. She gets disorientated, and falls … This story is told in stream of consciousness through the voices of Kate herself, her son Matt, her neighbour Alice, and mountain rescuer Rob. And frankly it got as tedious as Lockdown itself. The ending was suitably shocking, inconclusive and cliff-hanging, which redeemed it somewhat, but I doubt if this book will wear well.

So I’ll finish with another book set in the Cumbrian countryside: Helen Rebanks’ The Farmer’s Wife: My Life in Days. I met Helen Rebanks (wife of the more famous James, of The Shepherd’s Life fame) at another author-event at the Little Ripon Bookshop and found her sparky and interesting. I didn’t feel the same about her book. She details the hard slog of being a farmer’s wife and a mother in an unforgiving, if beautiful part of England. The book is interspersed with recipes, all of which can easily be found anywhere, and at the end are store cupboard hints which I doubt are of much help to her probable readership. An interesting enough but slightly disappointing read.

I’ve just read through this post, and see it has a slightly grumpy tone. It was slightly hastily thrown together today after our long journey back from Spain and dicing with farmers’ blockades in France, so I can’t claim to have given it too much thought. Next month, when the starter book is Ann Patchett‘s Tom Lake, Must Try Harder.

All images except the one of Kenneth Wilson cycling off with his cello in tow, which comes from the press pack on his own website, are from Unsplash, and are, in order, by Vlah Dumitru; Cajeo Zhang; Spencer Davis; Jonny Gios and George Hiles.

You must be logged in to post a comment.