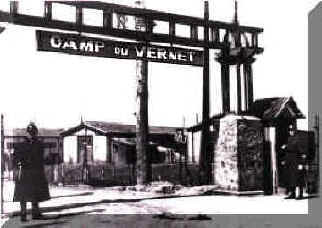

Yesterday, we visited one of the Ariège’s best kept – and most shameful – secrets, the museum commemorating the concentration camp at Le Vernet.

Yesterday, we visited one of the Ariège’s best kept – and most shameful – secrets, the museum commemorating the concentration camp at Le Vernet.

Starting in 1939, after the defeat of the Spanish Republic, the concentration camp at Le Vernet, near Pamiers, was used to detain the 12,000 Spanish combatants from the Durruti Division. At the declaration of war, ‘undesirable’ foreigners, anti-fascist intellectuals and members of the International Brigades were interned at Le Vernet under terrible conditions, described by the writer Arthur Koestler (himself interned there) in ‘Scum of the Earth’. In 1940 it became a repressive camp for interning all foreigners considered suspect or dangerous to the public order. At the time, it was known as ‘The French Dachau’.

From 1942 it served also as a transit camp for Jews arrested in the region. In June 1944, the last internees were evacuated and deported to Dachau in the ‘Ghost Train.’ In total about 40,000 people of 58 nationalities were interned in the camp.

We were shown round by the Mayor of le Vernet. He has a passion for sharing this dreadful part of French history which only someone whose family has suffered its consequences could have. He showed us the models of a vast camp, now totally obliterated, and the cramped dormitories.

He described the harsh conditions, when inadequately clothed and severely underfed men would have to stand outside, immobile, 4 times a day, during the extremely hard winters, for roll-call.

As a tiny baby, he was interned with his mother, a Spanish refugee, at a women’s and children’s camp, flimsily built and harshly managed, on the coast (Le Vernet was for men only). The women begged for clothing – their own was so flea-ridden it had to be burnt – and more food. The response was that they could return to Spain if they wanted. Some did, but many stayed.

As an adult, with a French wife and children, he wanted to take French nationality himself. ‘How did you arrive in France?’ ‘Via the concentration camp in Argelès.’ ‘There were no concentration camps in France, only accommodation centres.’ Such denial existed till quite recently – hence the total destruction of the site of this camp, the most repressive in France. Now however, largely because of people such as this mayor, the history of these camps, run and organized not by the Nazis, but by the French themselves, is at last being told.

You must be logged in to post a comment.