On the first Saturday of every month, a book is chosen as a starting point and linked to six other books to form a chain. Readers and bloggers are invited to join in by creating their own ‘chain’ leading from the selected book.

Kate: Books are my Favourite and Best

Set within a religious community in 9th century Germany, Emily Maguire‘s Rapture, which I have yet to read, reimagines the life of the first and only female pope.

It’s not too much of a stretch to travel to 7th century Ireland in Emma Donoghue’s Haven. Holy man Artt, recently returned from his travels, fetches up at a monastery with a plan to set forth with two of the monks there to set up a tiny community on a totally uninhabited island, to live prayerfully in total isolation. Imperfectly equipped, they soon embark on their journey into the unknown: and Artt insists on choosing not one of the nearby islands, but a distant one that is rocky, bleak, inhospitable. The tough character of this island, with its panoply of resident birds is brought vividly to life, as are monks Cormac and Trian. Artt remains as distant to us in many ways as he is to the two monks. This is a story that cannot end well, as a bad situation becomes worse. But it vividly brings to life the increasingly unbearable conditions made more difficult by a completely unapproachable and inflexible man-in-charge. It’s a quietly engrossing story.

A different remote island, at a different time – the 19th century. Carys Davies’ Clear is an engrossing book about a vanished way of life. One which disappeared during the devastating Highland Clearances in Scotland during the 19th century. A man Ivar, the sole inhabitant – with his few animals – of a remote island, is alive to the natural rhythms of the island – the many seasons, winds, mists, rains and tides that govern it. And when John Ferguson appears to evict him, but instead falls into a concussed coma from which Ivar nurses him back to health, he too falls under the island’s spell, and haltingly Ferguson begins to learn the vocabulary, then the language itself which Ivar speaks. The book celebrates that language and the fragility of life in such a spot, as well as asking questions about the future of Ivar, John, and John’s wife Mary, all of whom are in different ways implicated in the consequences of the Highland Clearance.

Yet another remote island – off Norway this time – present day Norway. Author and farmer James Rebanks was going through a tough time mentally. He needed to get away, and got the chance to stay in a remote and tiny island just below the Arctic Circle, where a woman was continuing the tradition, practised since Viking times of encouraging eider ducks to breed there, so that their valuable down could be harvested for warm clothing and quilts. This book is an account of the island’s astonishingly rich (but always diminishing) range of birdlife; its weather and relationship with the often unforgiving sea. Of how the woman and her friend, and that year Rebanks too, persuaded eider ducks back by building nests for them – yes, really! The protective down could be harvested from the nests when finally deserted, then cleaned and prepared for sale. It’s an immersive tale of a life that’s simple, often monotonous, always hard and often bleak, but with simple satisfaction too. The tale is told in The Place of Tides.

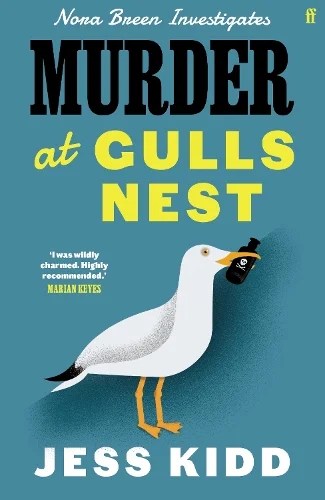

Let’s stay by the sea but lighten the mood, and read Jess Kidd’s Murder at Gull’s Nest. It’s Cosy Crime, and I don’t like this genre at all. But Jess came to speak recently at our local independent bookshop. She was a hit. She spoke wittily and enthusiastically about her career as a writer, and about this book, which is only the first of a planned series, following its heroine, a woman of middle years, plain and practical, Nora Breen. Nora links back to where we started from, because she was until recently a nun. But when her fellow nun and friend Frieda leaves the order, and then goes missing, Nora chooses this event as her reason to abandon her vocation behind and search for Frieda. She begins her search in a seaside town in the south, Gore-on-Sea(!) at a pretty dreadful boarding house (this is the 1950s) called The Gulls Nest, where Frieda herself had stayed till she disappeared, a victim in Nora’s opinion, but not that of the police, of Murder Most Foul. At first I was rooting for Nora, and enjoyed getting to know the half dozen or so other varied characters who populated this book . But improbable incident follows improbable incident. The book’s well written, but it isn’t enough to keep me invested in the events it described.

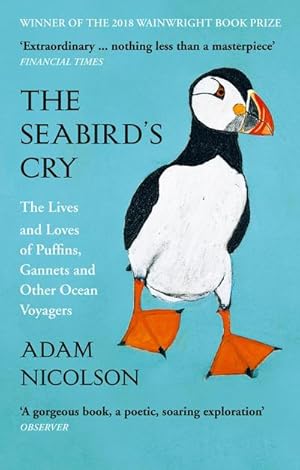

It’s too late now. I’ll have to stay with the sea for the whole chain, and this time, with gulls too. But let’s change the mood, and go with non fiction. Adam Nicolson’s The Seabird’s Cry. I unreservedly loved this book. Nicolson has long been fascinated by seabirds – not just gulls – and explains how these birds differ so much in habit and lifestyle from the garden birds with whom many of us are more familiar. Then he takes ten different species to examine in turn. He refers to his personal observations, to scientific research, to history and to literature to build a rounded and fascinating portrait of each species he’s chosen. My husband got used to having a daily bulletin of ‘today’s most fascinating seabird facts’ at breakfast each morning. Beautifully written, meticulously researched. readable and involving, this was a book I was sorry to finish.

.

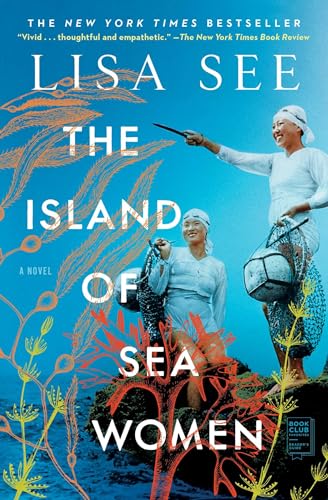

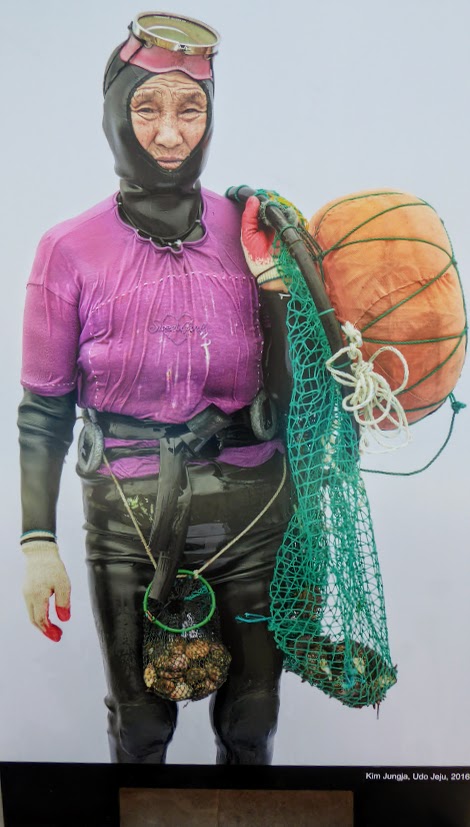

I’ll end in entirely another part of the world – South Korea, and take you to the island of Jeju, in Lisa See’s The Island of Sea Women. I had an immediate interest in this book, having travelled in South Korea – though we didn’t visit Jeju – and having already learnt to be fascinated by the lives of the haenyeo diving women. These are divers who harvest seafood (sea cucumber, urchins, abalone, octopus) all year round from the sea floor; they can stay underwater for sustained periods of time without breathing apparatus. This book combines a strong story following the story of two women Young-Sook and her mother, whose lives develop through their membership of the haenyeo culture, as they live through a twentieth century defined in Korea by occupation, internal conflict, deprivation and rapid change. Learning more about this history was in itself illuminating and interesting. It was a backdrop to a story of friendships, broken relationships and family struggle which drew me in to the last page. I was sorry to finish this book too.

It’s not clear to me how I got from a religious life in long-ago Germany to six books involving the sea. But Six Degrees takes us all to unexpected places. Where will next month’s starter book, All Fours, by Miranda July take us?

You must be logged in to post a comment.