For a couple of years now, I’ve more or less promised to take part in Novellas In November, a reading challenge celebrating short books – those coming in at under 150, or – stretching it a bit – 200 pages, hosted by Bookish Beck and Cathy of746Books. This is the first year of keeping that promise. And I haven’t over-delivered. I’ve read a mere five this month.

The first wasn’t even on my would-like-to-read list at all. I simply found it on the library shelf, and thought it looked worth a go.

Peace on the Western Front: Mattia Signorini (Translated by Vicki Satlow)

I’m not sure what to make of this book. It re-imagines the now well-known story of the Christmas truce of 1914, when English and German soldiers gathered in No-Mans-Land to share food and play football. For one day only.

It’s a tale that could not fail to be moving. And yet I felt the points that were being made were rather over-spelled-out: that Signorini told, not showed what was going on for these two young men. For me it was a slightly flawed giving of the message that war squanders young lives pointlessly, leaving nothing positive in its wake.

Having lived in the Pyrenees, and being a fan of Colm Tóibín’s writing made my next one a very easy book to pick up.

A Long Winter: Colm Tóibín

Set in an isolated village in the Spanish Pyrenees, this is mainly the story of Miquel. He lives with his mother and father – his younger brother is away on military service. They are largely ostracised because his father largely ignores his neighbours. After his secretly alcoholic mother vanishes in a blizzard, Miguel spends the rest of the winter searching for her body. He eventually has one single friend, the young man Manolo who comes to keep house for this undomesticated father and son, and helps him come to terms with his grief. The story is written in a clipped style, removed from emotional expression. I find though,it’s stayed with me . I explore the unexplained inner life of Miquel: I wonder if his relationship with Manolo becomes sexual – there are hints. A powerful story with much to think about from such a short novella.

Next, a novella translated from the Danish – and another powerful read.

The Wax Child: Olga Ravn (Translated by Martin Aitken)

This story takes us to 17th century Denmark, where on average, one ‘witch’ was burned every five days. This kind of event was mirrored all over Europe. Our narrator is a little beeswax doll, fashioned by a impoverished noblewoman, Christenze Krukow. Omniscient, she sees and hears all that goes on. How her maker is one of a group of women who work, and sing, and gossip, and practice the folk remedies they learned from their own mothers: who protect one another. The book is interspersed with spells and incantations which exist not to harm, but to protect; to prevent accident and disease; to bid others be kind; to divine if someone’s life may soon end. This solidarity among women is looked on askance by men ‘The woman is more easily tempted by Satan, for she is weaker than the man in body and soul … When a woman thinks alone, she thinks evil …’And so it comes to pass that several of these women are tried, found guilty …and die, horrifically. And yet this book is beautiful, horrifying, visceral, poetic. There is a sense of spells being woven on every page. The women in this story existed. They died as ‘witches’ and now they are remembered in this powerfully atmospheric and evocative re-imagining of their circumstances.

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Carte Blanche: Carlo Lucarelli (Translated byMichael Reynolds)

We’re in Italy, April 1945. The Fascist regime is crumbling, but the Germans are still in town. Life is violent, messy, disordered. Nobody knows whom they can trust. Commissario De Luca, who just wants to be a good cop, has just joined the Police ranks having transferred from the Political Police. He doesn’t want to get involved in politics. But how can he not? The latest murder victim is Vittorio Reihnard. He is well-connected, has lots of lady-friends, has a stash of drugs. And De Luca finds he can’t just get on with finding the perpetrator. He has to point the finger at whoever the political high-ups wish. It’s tense, breathless, cleverly revealing right-wing corruption and misdeeds. Here’s a nation seeking new moral bearings, and a cop who’s disillusioned and worn out. There’s a lot packed into just over 100 pages. There are however, two further books in the series.

⭐⭐⭐⭐

And finally…

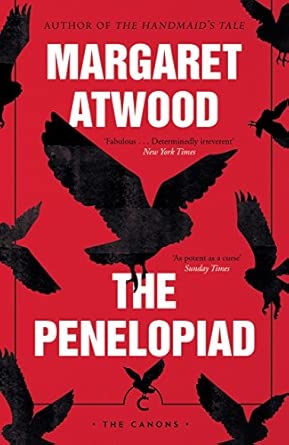

The Penelopiad: Margaret Atwood

Don’t tell anyone, but I’m not really a fan of Margaret Atwood’s writing, often finding it too dystopian for my taste. Recently, someone (was it you, Rebecca? suggested I try The Penelopiad. I’m glad I did. Most people know the story of king, soldier and adventurer Odysseus. Few people give much thought to his wife Penelope, abandoned during his long years away and forced to keep a constant stream of suitors at bay. This book puts that right. Now dead, Penelope wanders the Underworld, putting her own spin on events. She recounts her snarky relationship with the beautiful Helen of Troy. She details snippets about Odysseus’ doings: some describing the Homeric tales we read about, others giving a far less positive spin on his adventures. The narrative is interspersed with a Greek Chorus line of doomed maids: the ones whom Odysseus had killed on his return for their (unwilling) sexual alliances with Penelope’s suitors. Like Penelope herself, they are saucy, smirky, irreverent. A refreshing take on an extremely well-known legend.

⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Any other novellas this year? Well, yes, but only a few:

Seascraper: Benjamin Wood ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

French Windows: Antoine Laurain, translated by Louise Rogers LaLaurie ⭐⭐⭐⭐

Woman in Blue: Douglas Bruton ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐

Madame Sosostris & the Festival for the Broken-Hearted: Ben Okri ⭐⭐⭐

This last bit’s no novella. Well, it might become one I suppose. I needed a book for Becky’s NovemberShadows, and is was what I found.

You must be logged in to post a comment.