On the first Saturday of every month, a book is chosen as a starting point and linked to six other books to form a chain. Readers and bloggers are invited to join in by creating their own ‘chain’ leading from the selected book.

Kate: : Books are my Favourite and Best

The starter book this month is Michelle de Kretser’s Theory and Practice. I haven’t yet read it, but here’s something from the Guardian review: ‘In Theory & Practice, De Kretser gradually, delicately, picks and plucks at the notion of “truth” in literature…’

Well, here’s a book that looks at two kinds of truth, in Forty Autumns by Nina Willner. And it’s the story of her mother Hanna’s family she tells here. Her mother, aged 17, escaped from the newly-created and isolated East Germany, as Russia assumed responsibility for this area, while England, the US and France had West Germany. She did well, making a career, then marrying and moving to America. But her family was left behind, their lives increasingly constrained and isolated by the evermore authoritarian government there. She was able to have little contact with them, not even hearing when two brothers died. In the East, propaganda spoke of the degenerate and unsuccessful West, but prevented any contact. Her family – particularly her schoolteacher father – was under the government’s spotlight because they clearly were not uncritical party faithful. The fall of the Berlin Wall enabled them to reunite. The love remained, the contact blossomed, but the differences between their former lives cast a long shadow of bitterness and regret

Here’s another family dealing with differences among them, although of course, not the same kind at all. Albion, by Anna Hope.There’s so much to like about this novel: an evocation of a family, fractured in many ways, but coming together because of the death of its oldest member: father, husband and lifelong liar, bully and philanderer,Philip. A picture of an English country house (complete with a Joshua Reynolds family portrait) and countryside: now in the process of being re-wilded by father and eldest daughter in a project named ‘Albion’, – but had he actually wanted to hand the baton over to his son to continue down a different path, for wealthy ageing hippies? A younger daughter, married to a good man, re-kindling adolescent friendships and more with estate workers … or not? A resident ageing hippy … All this is so well painted. Enter Clara, who might have been Philip’s illegitimate daughter and who fetches up for the funeral. What happens from now on – but no spoiler alerts here – when Clara makes a dramatic revelatory speech, which in truth shouldn’t have been such a total surprise, totally changes the tenor of the story. What should have been a fine book is spoilt by this rather facile, bland and unsatisfactory last part.

Family difference is the theme in Forbidden Notebook by Alba de Céspedes, translated by Ann Goldstein.In November 1950 forty–three-year-old Valeria Cossati purchases a black notebook from a tobacconist – a ‘forbidden’ item as only tobacco could be sold from there on Sundays. This transgression informs the whole book. Valeria writes in her notebook only in secret: a good Italian wife devotes herself to home and family, without help from her husband or her two older children, both students. But unusually, Valeria also has a job, an office job. Her notebook becomes the place where she records her life, and that of her family. She vacillates between being critical and judgemental, and admiring. Her daughter enjoys freedoms she cannot dream of and in her diary she explores her conflicted feelings about this. Her son is academically lazy. Her husband calls her ‘mamma’. Her boss clearly finds her attractive, and she is not indifferent to him. All her tumult of feelings tumble onto the page of the book she must at all costs hide, because what if it were discovered and read? It’s a fascinating discourse in which we her readers feel as frustrated with her apparent acceptance of the role society has put upon her, as by her tangled ambitions to break out from these expectations. Her dreams are humble: to have space in the house for herself, and just a little time.

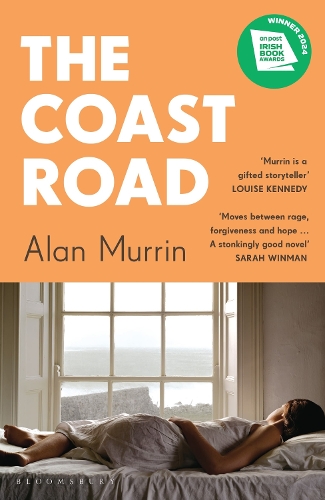

Another book about women and their families: The Coast Road by Alan Murrin. The novel, set in 1990s Ireland where divorce was still illegal, and revolves round three women (and Murrin is particularly skilled in bringing women to life) in different ways trapped by marriage, Colette – a bohemian poet – leaves her husband after her affair, and he won’t give her access to her youngest child. Dolores, married to a philanderer, is pregnant with her fourth child. Izzy has an ambitious and controlling politician as a husband.The lives of the three women become entwined as the plot develops, showing each of the men being unlikeable in different ways. Only Father Brian, the priest, comes out well. Here is a novel describing vulnerable, limited lives held in check by fear of scandal. Characters are all brought convincingly and sympathetically to life. Murrin seems to know well the world about which he writes, and even the ending, highly dramatic as it is, is believable and compelling.

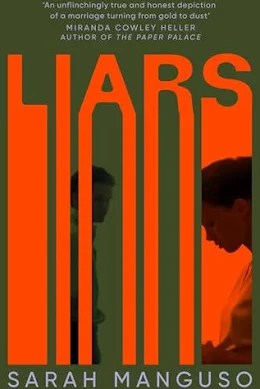

And here we are again. Difficult family life, in Liars by Sarah Manguso. This is the story of Jane, writer and academic, who as a young woman meets John, a charismatic film-maker. They set out to construct a creative, equal marriage and apply together for artists’ fellowships, only for Jane to succeed and John to fail. At this early stage the warning signs are there. John fails and fails again, but they marry anyway. When they have a child together, Jane is doubly trapped. She and her (unnamed) son are dependent, because of the shrivelling of her career, on John’s income. The reiteration of a pattern, year after year after year is debilitating all round and exhausting to read about. Jane is increasingly a victim, increasingly two-dimensional. Finally – finally – John leaves them. A somewhat depressing book, in which the characters – there are only two really, as The Child only develops some kind of personality towards the end – deny the readers the possibility of liking them, or in my case, caring very much about them.

My last book, a series of short pieces, also often focuses on relationships: the mother and child. Jamaica Kincaid’s At the Bottom of the River,also writes about the natural world and achieving independence. The language is beautiful – often hauntingly so. There’s often wry humour: the first essay of all is a list – a long list – of how the daughter should behave in order not to become a slut. The entire piece is one sentence long… ‘This is how you iron your father’s khaki shirt so that it doesn’t have a crease; this is how you iron your father’s khaki pants so that they don’t have a crease; this is how you grow okra – far from the house, because okra tree harbours red ants ….‘This was perhaps my favourite piece. Kincaid is very good at lists, and this one is the first among several that contain them.

Nevertheless, I didn’t find this easy reading, and I often struggled to follow the drift. I hugely enjoyed Kincaid’s use of language, but remained puzzled by the book as a whole.

So there we are. A chain about relationships: which is the theme of most fiction, I guess. And next month’s starter book is The Safekeep by Yael Van Der Wouden. Kate’s review makes it sound an appetising read.

And here, nothing to do with this challenge, but everything to do with Becky’s Squares Challenge, #SimplyRed, is a surprise find in a flea market in Barcelona. Who knew that Just William was popular in Spain too?

Photo Credits:

Own photo

Own photo

Evgeny Matveev: Unsplash

Own photo

Siona das Olkhef: Unsplash

Segi Dolcet Escrig: Unsplash

You must be logged in to post a comment.